Lemon Cash is a crypto startup based in Argentina that operates digital wallets, card payments and more. In this blog post I describe how we implemented a solution for provisioning, deploying and operating services that empowers developers to ship more quickly. This solution is not a fully fledged platform but it provides similar benefits by standing on top of strongly defined concepts and conventions. What we implemented only makes sense in the context in which the company was in, so I will start by explaining what that context was.

Background

In April 2022 the company found itself at a stage many startups face, they grew really quickly without dedicated focus to infrastructure and developer experience. This means no explicit cloud networking architecture, a monolithic application deployed on ECS, a few lambdas, an RDS database and a collection of custom scripts and github actions for deploying things.

At that point the company decided to build a small team of Infra/SRE and Engineering Effectiveness that will tackle all things infrastructure and other big projects such as Breaking the Monolith. Before actually being able to deploy new services and break the monolith we realized that we needed to implement a “proper” cloud networking architecture along with a standardized way of provisioning, deploying and operating services. I will focus on the latter and leave the details of our networking architecture for a separate post.

DX First

When we set out to solve this problem we wanted to make sure we provided the best Developer Experience possible. We decided to go with a CLI, called lemi 🍋, that acts as the interface for all thing services. In the end, we want developers to provision a service by just running:

$ git checkout -b provision

$ lemi service new --service example --cpu 512 --memory 1024 --desired-count 3 --owner infra

$ git commit -a -m "Add service definitions and CI workflows"

$ git push -u origin provision

After that we want them to use this same CLI, lemi, to operate on their services and do things such as:

# exec into the service's container

$ lemi service exec -s example

# restart their service

$ lemi service restart -s example

# deploy an image

$ lemi service deploy -s example --tag <image-tag>

Concepts and conventions FTW

Convention over configuration. This is something I internalized while working with Ruby on Rails a few years ago. It is incredible how much work you can not do by relying on strong conventions that do not compromise the functionality you want to provide. Coupling this with clear concepts that separate concerns allowed us to develop something very quickly while keeping a lot of simplicity.

Concepts

We started by separating Static from Dynamic Infrastructure. Static infrastructure are components such as Databases, Caches, VPN/VPCs, Lambdas, S3 buckets, Service Resources and others that require more explicit provisioning and are not changed that frequently. While Dynamic Infrastructure are things that are closer to the service itself and developer teams. They can possibly change with every deployment and should be owned and controlled by the teams themselves. This includes things like: Service versions, Observability, Routing, Access Control and pipelines. We make this distinction because we believe there different needs for each type of infra. For the case of Static Infrastructure we want to make sure that:

- Is always reproducible,

- All changes made to it are tracked through git and IaaC,

- Ownership of resources is explicit and clear,

- Tagging is effectively made to allow for observability and cost ownership.

For the case of Dynamic Infrastructure the goal is to have it as close to the developers as possible. This means that they have full control over it and are able to work and iterate on it without the need of the infrastructure team stepping in.

With these concepts in mind we landed on something we are comfortable with and gives us a lot of room for improving. We have a central terraform repository that holds all of our Static Infrastructure. This central repo is owned and controlled by the infrastructure team. However, through the use of terraform modules provided by us, developer teams can very easily (and without a lot of terraform) define new infrastructure that accompanies the services they are deploying. For the Dynamic Infrastructure we provide a YAML abstraction that defines what a service is and is owned and developed by the teams themselves. This abstraction exists mainly because at the moment we are using ECS. While the platform is useful in many ways, it does not provide clear APIs that can be easily exposed to developers. We coupled this service spec with the definition of environments and their corresponding variables, secrets and parameters. The important detail is that these files live in the repository of the service itself and are owned and controlled by the developers.

Conventions

The conventions that we define below allowed us to remove instead of solve many problems that don’t really limit the functionality that developers end up having and does not compromise what can be achieved. This conventions, and the problem they solve, are:

- Routing: all services are available internally through a global Application Load Balancer using Host-based routing and the name of the service as a part of our URL:

<service-name>-internal.<environment>.lemon. - Service Discoverability and naming collisions: the name of the service is the name of the repository. Since GitHub can’t have two repositories named the same way there won’t be any collision. Coupling this together with what was defined above for routing you can easily find which services exist in our infrastructure today.

- Transport: services have to expose an HTTP API on port 8080.

- Observability (metrics, tracing and logs): Services have to expose an endpoint

/metricson their 8080 port that holds OpenMetrics metrics. As for tracing, all services are shipped with a Datadog sidecar that provides logs and traces out of the box and automatically exports the metrics to datadog. - Packaging: Docker has to be used to package the service.

- On Call & Service Ownership: the owners of the repository are the owners of the service and are in charge of operating it and being on call.

- Testing: we used JVM-based languages and gradle. To simplify our pipeline services have to implement three commands:

./gradlew test,./gradlew integrationTest,./gradlew e2eTest.

To simplify the work developers have to do, they only have to implement the convention for Transport and Testing. lemi, our CLI, takes care of all the rest: Routing, Naming, Observability, Packaging and Service Ownership (by relying on GitHub permissions).

Provisioning, Deploying and Operating a service

I already threw a lot of text at you so instead of explaining things further let’s have some fun by going through a demo of what developers actually do when working with services at Lemon, let’s add some screenshots too! 📸.

Provisioning

To simplify the demo we will assume a developer already has a part of the service developed, this means that there already is a GitHub repository that has the branches we use at Lemon: main for production and develop for staging (our testing environment).

We start working from main. To start the provisioning process we go back to the first part of this blog post and run:

# first we checkout a new branch were we will add all the files generated by lemi

$ git checkout -b lemi-provision

# now we simply create a new service by running the following command

$ lemi service new --cpu 512 --memory 1024 --owner infra --service demo-service --desired-count 1

# run git status to see what lemi actually added

$ git status

On branch lemi-provision

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

.github/

deploy/

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

As you can see in the last command, lemi added two new folders: deploy/ and .github/. Inspecting first deploy/ we can see that it created the service.yaml definition we previously mentioned along with two files, prod.yaml and staging.yaml, that hold the environment variables, secrets and parameters for each corresponding environment:

$ tree deploy/

deploy/

└── demo-service

├── environment

│ ├── prod.yaml

│ └── staging.yaml

└── service.yaml

2 directories, 3 files

Let’s take a look at the specification of the service by looking at service.yaml:

name: demo-service

owner: infra

spec:

desiredCount: 1

image: demo-service

resource:

cpu: 512

memory: 1024

This is a very simple spec, mainly because the requirements we have are clear and some of the conventions allow us to not provide additional config parameters. We only have to define the service’s name, owners (used for cost ownership) and the spec that holds the resources the service requires.

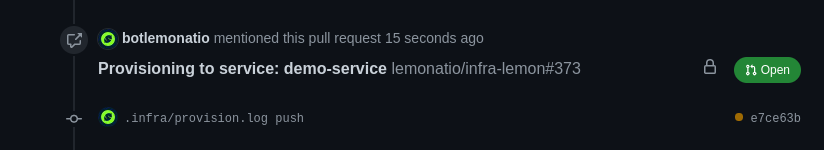

With that out the way, lets actually try to provision our service. For this all we have to do is commit, push and create a PR on GitHub. With the PR created we will see something interesting happen. There is a link, that was automatically added, pointing to a PR on our central terraform repository:

If we follow the link we can see what the PR is actually attempting to provision (this is the static infrastructure):

module "demo_service_ecs" {

source = "git@github.com:lemonatio/infra-ecs-module.git"

owner = "Infra"

name = "demo-service"

networking = local.networking

load_balancers = local.load_balancers

}

The interesting part here is the ECS module itself we provide. This module abstracts away all the complexity that provisioning an ECS service has and implements some of the conventions we defined previously, the most important one being routing and ingress rules that make this service accessible from within our infrastructure and from the internet. This module is closed source and I cannot share the implementation here unfortunately.

With this PR created, developers can add any additional Static Infrastructure that they need. For example, if their application requires an ElastiCache instance it could easily be added here using our modules as well:

module "demo_service_ecs" {

source = "git@github.com:lemonatio/infra-ecs-module.git"

owner = "Infra"

name = "demo-service"

networking = local.networking

load_balancers = local.load_balancers

}

module "demo_service_redis" {

source = "git@github.com:lemonatio/infra-redis-module.git"

name = "demo-service-redis"

owner = "Infra"

networking = local.networking

service_sg_ids = toset(module.demo_service_ecs.default.network_configuration[0].security_groups)

}

You may be wondering how did this happen? lemi FTW! If you remember when we run the lemi service new command we showed that lemi added some github workflows within .github. One of those workflows is provision.yaml and takes care of everything we just saw. The important part of it is that the workflow does not do any magic, it only orchestrates functionality that lemi itself provides. The important part of the workflow is this right here:

- name: Infra provisioning

env:

GH_AUTH_TOKEN: ${{ secrets.LEMONATIO_BOT_TOKEN }}

run: |

./lemi-latest provision --prId ${{ github.event.number }} --repoName ${{ github.event.repository.name }} --currentBranchName ${{ steps.branch-name.outputs.current_branch }} --service demo-service

As you can see we are using a command that lemi provides: lemi provision <flags>. The rationale for this is that we want to make sure that all of our operations that happen on our CI can be also tested and run locally. If for some reason we stopped using GitHub Workflows, developers could still simply run this command on their local machines and the entire process would continue to work.

This PR will be reviewed and approved by the infra team. Once it is merged the corresponding PR on the service repository will be automatically merged and the service will be considered provisioned!

Now let’s move along to doing our first deployment.

Deploying

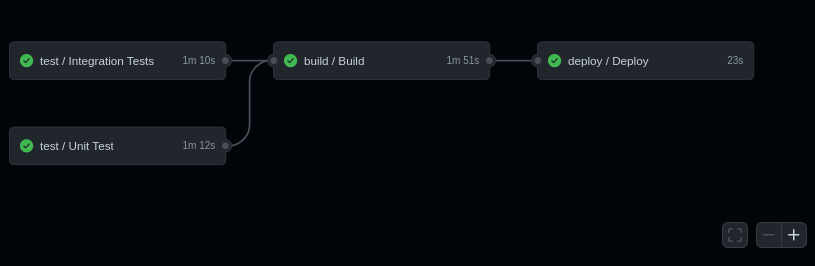

As was previously mentioned we have two environments at Lemon: production (deployed from the main branch) and staging (deployed from the develop branch). When we executed lemi service new, lemi generated the provisioning workflows along with all of our building, testing and deployment workflows. Let’s inspect staging’s deployment workflow to understand how things are deployed:

name: Deploy to staging

on:

push:

branches:

- develop

jobs:

test:

uses: ./.github/workflows/tests.yml

build:

uses: ./.github/workflows/build.yml

needs: test

with:

image-tag: ${{ github.sha }}

ecr-repo: demo-service

secrets:

region: ${{ secrets.AWS_STAGING_REGION }}

access-key-id: ${{ secrets.AWS_STAGING_ACCESS_KEY_ID }}

secret-access-key: ${{ secrets.AWS_STAGING_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY }}

deploy:

uses: ./.github/workflows/deploy.yml

needs: build

with:

image-tag: ${{ github.sha }}

service: demo-service

environment: staging

lemi-bucket: infra-lemi-staging

secrets:

region: ${{ secrets.AWS_STAGING_REGION }}

cluster: lemon-ecs-cluster

access-key-id: ${{ secrets.AWS_STAGING_ACCESS_KEY_ID }}

secret-access-key: ${{ secrets.AWS_STAGING_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY }}

The first important thing is reusability! You can see that each step (build and deploy) is triggering a different workflow and specifying a series of parameters that are specific for this environment. This allows us to have a single workflow that is reused across environments.

Let’s now look into the deploy workflow since the build is rather simple (build the dockerfile and publish to ECR). The process itself is quite large, so lets only look into the relevant parts, this are the ones controlled again by lemi:

- name: Verify service spec and provisioning

id: verify-service

env:

SERVICE: ${{ inputs.service }}

CLUSTER: ${{ secrets.cluster }}

run: |

./lemi-latest verify -s=$SERVICE --cluster=$CLUSTER --check=spec,provisioned -e=$ENV

- name: Compile task definition

id: compile-service

env:

IMAGE_TAG: ${{ inputs.image-tag }}

SUFFIX: ${{ inputs.suffix }}

SERVICE: ${{ inputs.service }}

ENV: ${{ inputs.environment }}

run: |

./lemi-latest compile -t=$IMAGE_TAG -s=$SERVICE -e=$ENV

cat task-definition.json

- name: Deploy service with new task definition

id: deploy-service

env:

SERVICE: ${{ inputs.service }}

CLUSTER: ${{ secrets.cluster }}

SUFFIX: ${{ inputs.suffix }}

run: |

./lemi-latest deploy -s=$SERVICE --cluster=$CLUSTER

We have three key steps defined here:

lemi verify: this command runs a series of validations to make sure that the deployment can indeed be executed. This validation checks the service, secrets and parameters are all provisioned on the corresponding environment and validates that theYAMLis correct and has all required parameters.lemi compile: with theservice.yaml, the corresponding env file (i.estaging.yaml) and the ECR Image tag we compile it down into an ECS task definitionlemi deploy: using the task definition created in the compilation process, we register a new revision and update the service to point to this latest version.

As it was shown in the provisioning process previously, all critical operations are done by lemi and GitHub simply orchestrates the execution of it. This means that any developer can run this commands on their local machine if needed.

With this workflows in place all commits sent to develop will be automatically deployed to staging and those that go to main will be deployed in production:

Operating

Last but certainly not least, we want to provide a unified way of operating services at the company. This is mainly because we are not a big company and switching between teams that own different services is completely normal. So if a developer goes from team A to team B, they are already familiar with how to operate their services in our environments. This is why we built a series of commands into lemi that developers use. A few operations that developers usually do:

# restart the service using a graceful deploy of the same image

$ lemi service restart -s demo-service -c lemon-ecs-cluster

# list all running tasks the service has

$ lemi service list-tasks -s demo-service -c lemon-ecs-cluster

["arn:aws:ecs:us-east-1:<AWS_ACCOUNT_ID>:task/lemon-ecs-cluster-prod/77c0048e9f3a4e04ae6b35c89270acdd","arn:aws:ecs:us-east-1:<AWS_ACCOUNT_ID>:task/lemon-ecs-cluster-prod/91a67a2f88b542e4a8c30f2c6290d80e","arn:aws:ecs:us-east-1:<AWS_ACCOUNT_ID>:task/lemon-ecs-cluster-prod/d02725effb574e96847b4abe21740987"]

# stop a specific task

$ lemi service stop-task --task-id arn:aws:ecs:us-east-1:<AWS_ACCOUNT_ID>:task/lemon-ecs-cluster-prod/77c0048e9f3a4e04ae6b35c89270acdd

# exec into the container of the service, useful for when things go wrong and we want to do closer deep dives

$ lemi service exec -s demo-service -c lemon-ecs-cluster /bin/bash

running /bin/bash on task arn:aws:ecs:us-east-1:<AWS_ACCOUNT_ID>:task/lemon-ecs-cluster-prod/77c0048e9f3a4e04ae6b35c89270acdd

Starting session with SessionId: ecs-execute-command-0730176e68438b66d

root@ip-172-19-0-73:/#

We have more commands available for inspecting the service, understanding the status of a deployment, etc. As developers need specific operations we can quickly develop them since they are wrappers over AWS’s API.

Looking forward

We understand that what we built here is rather simple but we believe it solves a big pain we were facing and lays a very strong foundation for future requirements we may have. One of the big discussions that we are going to have in the short term is whether we want to stick with ECS or not. While it certainly has good functionality and is the right tool for many use cases, we are starting to hit some of its limitations and they are starting to hurt. When we started with this idea we had a short conversation on whether we wanted to stick with ECS or not, but since we were (and are) short staffed with a lot of important things to tackle we decided to leave that discussion for the future. While this may change some details of this process we believe that the concepts and conventions will remain.

What are our next steps? For now we are focused on other projects, the biggest one was mentioned previously and is the breaking of the monolith. We are an infrastructure and Engineering Effectiveness team which is why we are the owners of it. We believe that as we have more services we will encounter use cases that will force us to adopt and develop new and exciting things, so we can’t wait!

Remarks

Thank you for sticking until the end! We have many exciting projects going on and more blog posts may come to this blog. While I’m the one writing this, I’m not by any means the only one that should receive credit for this work. I wanted to mention Claudio Martinez and the entire Infra/SRE team at Lemon Cash because without them this blog would not exist 😁